Reinventing Instruments to Reinterpret the Past and Question the Present: Patricia Alessandrini in Conversation with Nicholas Moroz

November 2017

This autumn Explore Ensemble and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival have co-commissioned Patricia Alessandrini for a new work. The resulting creation was Tracer la lune d'un doigt (to trace the moon with a finger) for augmented instruments, and was presented at HCMF on 23 November 2017 with the support of Arts Council England, PRS Foundation, and Goldsmiths. It was recorded live by BBC Radio 3 and subsequently broadcasted on the Hear and Now Programme on 16 December 2017. Simon Cummings, writing on the 5:4 blog, hailed Alessandrini's work as 'One of the most beautiful things I’ve heard at HCMF this year, and further proof positive that Explore Ensemble are just as indefatigably outstanding as we all suspected last year'. Tracer la lune d'un doigt augments the ensemble instruments, especially the piano, to reinterpret the musical past, and specifically here the adagios from J.S. Bach's Violin Concerti. This article documents our project with Patricia, and more broadly introduces her artistic language.

See this video produced in partnership with Goldsmiths, University of London, which introduces Patricia's artistic research, with footage from our workshop with her new work in early November 2017.

Abridged interview from talk given at the JdP Music Building in Oxford on 24 November 2017

NM

We've all been fascinated by the new robotic piano interface that you've developed for your Explore Ensemble commission. Could you tell us more about it?

PA

I created this in collaboration with the head of our fabrication laboratory at Goldsmiths, Konstantin Leonenko. The machine is using physical computing techniques. I’m using the computer not to make sound but rather to make something move, as in robotics or physical computing. With the machine, there are tiny acrylic fingers that sit between two of the three strings for each note of piano (or between two strings in the lower register). Each finger is then attached to a motor, derived from the vibrating mechanism found in mobile phones, and activated by a MIDI keyboard which sits on top of the piano.

In addition to the motors, the whole piano is wired up to create a feedback system. Using several transducers, the sound is then re-transduced back out into the piano, where it’s picked up again and continues in the feedback loop. It focuses on the bass register, so that whenever the pianist holds down notes in the lowest register the resonance feedback sound starts, and as soon as you release those keys, the sound fades away. The sound of some instruments of the ensemble are also fed into the piano resonance system, such that they are able to make the strings of the piano resonate as well.

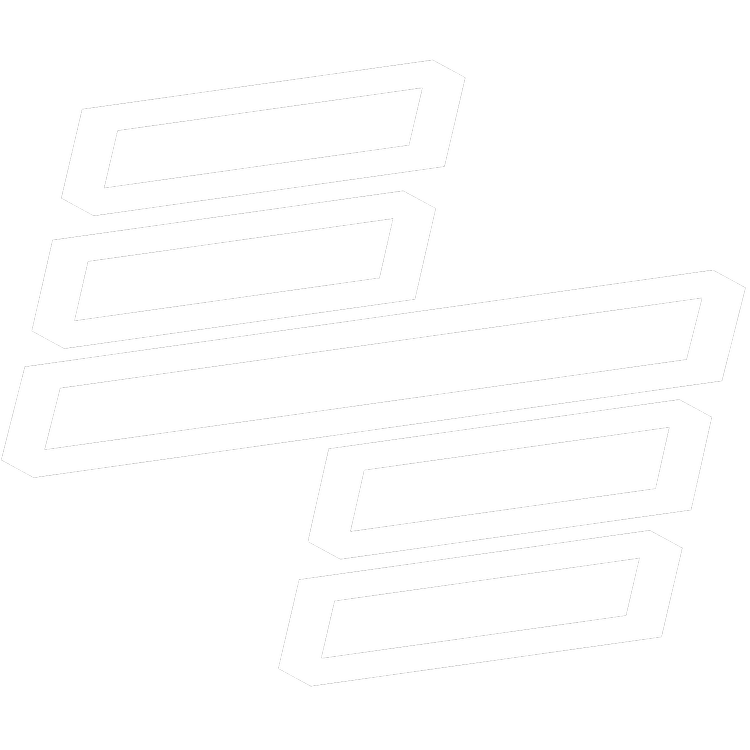

Patricia Alessandrini. Tracer la lune d'un doigt (2017), page 5

NM

Can you explain the significance of the title, 'Tracer la lune d'un doigt'?

PA

The title relates to the relationship between the imaginary and the physical: I use electronics to try and create an imaginary situation that relates to the physical world. Here, as the title suggests, it is the distant celestial body of the moon that I want to try to reach out and touch; for me, this celestial body serves as a metaphor for the music of Bach. It’s the first time I’ve engaged in this way with Bach, perhaps because it’s been a somewhat intimidating idea, but in this piece I came to look at the Adagio movements of his Violin concerti. In this composition, one may hear extremely suspended versions of these works, however they are stretched in time in a rather free way so that there are occasionally pauses where moments from different excerpts are frozen, before they continue on, and they may blend into one another as well.

Programme Note

The title – in English, 'to trace the moon with a finger' - calls up the act of attempting to apprehend an abstract beauty: a distant, cool and pale yet luminous object.

A small child sees a moon in a storybook and traces its outline with her tiny finger. The circle she touches is indelibly connected to the distant body which cannot be touched: without knowing the word 'moon', she has touched the moon and re-drawn it.

Most of my works consist of 'interpretations' or 'readings' of existing repertoire. For this piece, I decided to 'read' the Adagio movements of J. S. Bach's violin concertos, to try to understand something about their expressivity in relation to style and convention. This came about from re-watching Jane Campion's The Portrait of a Lady, in which the use of diegetic music – i.e., music whose presence is produced in the film itself, directly on-screen or off-screen, as opposed to a soundtrack whose direct sonic origin is not represented in the film – is key. (Lawrence Kremer has written about her diegetic and non-diegetic use of Schubert in the film in an article entitled 'Recognizing Schubert: Musical Subjectivity, Cultural Change, and Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady'.)

The Adagio movement from BWV 1041 accompanies a scene of frustrated young lovers, whose relationship is limited by traditionalist conventions and the young woman's forced submission to her father's authority. The function of the music is multiple: while its style evokes 'Baroque' conventions of social relations – much as Mozart used the Baroque style to designate oppressive and archaic practices in The Marriage of Figaro – there are undoubtedly expressive qualities of the music beyond its stylistic associations which set the scene, as the regularity of the rhythm and repetition of the phrasing creates a sense of expression which is all the more poignant for its restraint.

After having completed recent projects dealing either with music and semantics or with specific social and political issues, it is this sense of restrained expression based on 'abstract' material that I wish to touch upon in this piece, using somewhat limited means. The instrumentalists' expressive possibilities are limited to a paler palette through a restricted vocabulary of techniques, connected up through a system of electronics which 'reads' these techniques, interprets them, and 'performs' them itself through devices which cause the instruments to vibrate, in particular by 'playing' the strings of the piano.

I wish to thank Ensemble Explore and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival for the opportunity to compose for this wonderful, up-and-coming ensemble, and explore some experimental electronics techniques in the process.

Patricia Alessandrini. Tracer la lune d'un doigt (2017), page 14

NM

What motivates you to work directly on history and the musical past?

PA

I’m somewhat of the opinion that nothing is new, or rather that anything new is just a recombination of things that already exist. This contrasts with the idea of firstism, which you encounter a lot when working with technology (Georgina Born writes about this). I try to emphasise and embrace this idea of nothing being new, but where difference is still possible, and this difference comes about through my subjectivity as a performer, as an interpreter of what has come before. So interpreting the past is partly motivated by the idea of composer as performer, but it's also me wanting to move away from style.

When I was starting out as a composer, probably like many others, I was preoccupied with making "beautiful" material. But I came to realise that this material may serve as a marker for style, which may lead to you being put into a category, and I was horrified by this idea of schools of composition and belonging to one or another; in a way it seems rife for exclusion and violence.

I often look to visual artists like Robert Irwin and Gerhard Richter as possible models. What I particularly like about Richter is that whilst going through all these different methods of production he maintained the same ethos. In one of his writings he said “style is violence, and I am not violent.” That’s something I come back again and again to: and in a way, I want to try to make my music style-less, as anyway the material is coming from Mozart, Bach, always from somewhere else.

I feel that as composer I’m actually performing and interpreting the past through different technologies. Probably the clearest example of this process among my compositions would be the kinetic installation Adagio sans quatuor (2010), which is based on the Adagio introduction of Mozart's “Dissonance” quartet. It’s quite a striking introduction since it differs so much from the rest of the movement, also in it’s sense of suspension, and as I wanted to create a work about this sense of suspended time I was drawn to this particular piece.

I found numerous recordings, and also made some new ones at IRCAM with the Quatuor Diotima, whom I asked to interpret the work in different ways for each take. Then I proportionally time stretched these recordings note by note, such that the combination of them gave the effect of many quartets playing together at the same time, each with different variations of vibrato, intonation, and expression, in addition to the ambiances and recording artefacts particular to each recording. Then I transposed this (somewhat monstrous) combination of recordings down a few octaves without time correction, rather as one might slow down a tape recording. This produced an extreme time-stretching, from the average recording of about a minute and a half to roughly twenty minutes.

I took this material and played it through suspended metal plates and instruments designed by my Sonic Arts Research Centre colleague Paul Stapleton, the latter of which were slowly bent by motors. In this sense I replaced the four players of the quartet with four plates suspended in the space. The orchestration of the recorded quartet material was determined by the physical characteristics of the plates and instruments themselves, as their resonant properties lent them different propensities to different frequencies. Essentially you can tune the plates by bending them to make them more sensitive or sympathetic to certain frequencies. I then used some modified speakers to transduce the prefabricated sounds through the instruments made by Paul Stapleton and the metal plates.

The plates are made of different materials including bronze and stainless steel, and are bent by the motors which are controlled along with the playing of the sound samples. At the time I was inspired by the work of Anish Kapoor, who makes sculptures that explore very slow types of movement, and so I thought that the slow movement of the bending plates would work well with the slow sound samples I had already created.

In the middle section the plates are quite bent and the sound samples are also fairly high in register. This is also where one of the fastest melodic lines from the original adagio appears, and so it’s here that I feel it’s possible to recognise the Mozart the most. In the original Adagio there is a concluding G major chord, and when this chords ends in the recordings, I extend the harmony with a low G sine tone resonating into the plates. So right at the end I allow the plates to make lots of free micro movements, very small and rather slow, which creates subtle modulations of the low G sine tone. I also planned to model the sizes, weights, materials, and densities of the plates so that two of them were tuned to a fundamental on G (more or less), but there was also a bit of serendipity with how things worked out, so that the single sine tone produces a rich array of sounds certain bent positions. The idea of this ending section was to let the plates be their physical selves, and thus to let them modulate the (very basic) material according to their physicality.

NM

Do you make a particular distinction between your work as a sound artist and as a composer, or what's in common to both?

PA

I have both scored and unscored pieces, probably more of the former. What I usually do as a process in either instrumental or installation work, as you see in the quartet above, is take materials from existing recordings to make what I call a maquette. In the installation of Adagio sans quatour you actually hear this directly, filtered through the instruments and plates. In other cases the maquette also ends up somewhere in the electronics, but the most important thing is that the score for the instruments comes from a transcription of the maquette. In this sense I start my instrumental works as electroacoustic pieces in order to eventually produce the score.

In the last few years I’ve written mostly scored works, including one instrumental work without electronics for the Arditti Quartet, entitled Forklaret Nat (2012). In this case I was thinking of the Arditti Quartet’s grounding in repertoire that comes out of the Second Viennese School. I thought it would be interesting to take an iconic piece from this world, and so turned to Schönberg’s Verklärte Nacht. The title - Forklaret Nat - is a homophonic translation of Verklärte Nacht. At the time I had been doing some work in Denmark and was very interested in the Danish language, so here the title ended up being words from Danish that sound like Verklärte Nacht. ‘Nat’ means night but ‘Forklaret’ means ‘explained’, so it’s ‘night explained’.

PA

In a way it’s me trying to understand Schönberg’s aesthetic but also the significance of the Second Viennese School and their influence as observed not only in the Arditti Quartet’s repertoire but also in a lot of other contemporary music ensembles. I was particularly interested in the darkness of this aesthetic, which of course has its particular historical context, but also about how it translates for us today and how we can relate to it, so in a sense this relates to this idea of explaining, as the title says.

What also fascinates me about Verklärte Nacht is how it’s on this cusp of atonality and how its form contrasts between two major/minor parts that reflect the original poem of Richard Dehmel. Also, the moment of transfiguration and lightening of the previously dark anxiety of the piece, which is also typical of that kind of expressionism that dominates much of the Second Viennese School’s musical aesthetic.

So with Verklärte Nacht I took both halves of the piece, using various recordings, and then folded it over on itself: I reversed the second half and superimposed it onto the first half. A strange thing happens at the end, where instead of reaching the final transfiguration you hear both the transfiguration and what comes after it at the same time. In this case the samples from recordings weren’t time-stretched but just reversed. Ashot Sarkissjan, the second violinist of the quartet, was always listening and trying to work out these backwards melodies! Since the music was backwards (this is a maybe little literal-minded of me) I wrote a lot of the string playing with bowing behind the left hand, which masks the notes somewhat as it makes the instrument less resonant.

NM

The sounds and melodies of the quartet have these smeared or disfigured timbral and temporal qualities, how do you create them?

PA

This is one of the cases where I referred back to the score of the source material. Sometimes the backwards playing is in fact the originally melody notated in retrograde, but more importantly I make a spectral transcription of the piece. I could use the notes in the score, but I prefer to take the recordings and represent them by spectrally reconstructing them.

NM

So it’s not only Schönberg’s notes but also the timbral particularities of performers’ recordings that interest you in creating harmony and timbres; does this reflect your approach with electronics?

PA

Exactly, like a lot of spectral composers I’m not just looking to represent a fundamental but rather I’m trying to rebuild the timbre by combining many partials. Most of my works have live electronics, but like in the installation I like to have a strong physical image of what’s happening in the electronics. With electronics one can make almost anything, there are so many possibilities. I try to narrow these down by creating a physical image. Reflecting, for instance, on our experience of acoustic instruments, with electronics I want to create something that’s similarly rich and evocative.

An example of this is my guitar and electronics work Menus morceaux par un autre moi réunis (2009). I worked a lot with the guitarist Mauricio Carrasco in exploring different techniques, and considered using some kind of attachments to the guitarist’s hands or arms, a bit like how, for example Michael Finnissy in some pieces attaches bells to the pianist’s or percussionist’s wrists, so that every movement that they make create this jingling sound.

Since Mauricio was showing me this scrubbing sound on the strings I thought about adding bells on his wrist, or using the electronics to create that somehow. He was also doing left-hand tapping on and off the string, so imagined there to be larger bells hanging off his left hand, or on the neck of the guitar. Instead of using real bells, using the electronics I could constantly tune the virtual bells so that there were myriad different bells of different shapes and sizes, and this by using physical modelling techniques. This is where you can code a virtual object to sound in various ways, often in ways that would be nearly impossible or impractical to realise in reality. This is strongly related to how the plates work in Adagio sans Quatour, but whereas the plates were physical with their own properties, in Menus morceaux I take those physical properties and synthesise them.

NM

I notice that you often use scordatura on string instrument in your works. How do you decide on particular tunings?

PA

The scordatura come about partly to correspond to the harmony created in the spectral transcriptions that I make. In this case Menus morceaux comes from Debussy's Chansons de Bilitis, and I think there’s something in the harmony supplemented by the virtual bells that reflects this. Also in this piece, there’s a microphone in the sound hole of the guitar, and the frequencies of the bells change depending on what is played live.

Using scordatura is also about resonance. Musicians are usually trying to create perfectly resonant beautiful sounds with their instruments, and in a way I’m de-optimising their instruments, since the scordatura will cause them to resonate differently, and more generally changing the resonant properties of instruments is something that interests me a lot.

NM

That brings us back to your idea of augmenting instruments, which is also part of your piece for Explore Ensemble. How did this begin?

PA

Thinking chronologically, Menus morceaux was just before the installation of Adagio sans quatour, and although I was very happy with the guitar piece, I do feel a certain frustration with diffusing sound through loudspeakers. As an electronic music performer I work on a lot of repertoire with different musicians, and there’s always a struggle to amplify the instrument whilst maintaining a good balance between acoustic and electronic sounds, as well as many other practical issues. Then with the installation, what I liked about it was how you could create your experience of the sounds by moving freely around the plates, as if you're inside the quartet. This led me to ask, how can I create more of this beautiful instrumental radiation of sound? As the plates were driven by transducers I then started transducing through instruments. Perhaps a good example is my work Hommage à Purcell, which is a work for instruments and electronics that I revised so that all of the electronics are transduced through the piano.

NM

Who else was using transducers like this?

PA

It’s an interesting question. I think that now it’s become fairly common practice, but when I was working on the installation in 2010 at IRCAM there were no transducers around. There were some people working with modified speakers, for instance Juan Cristobal Cerrillo created an installation for snare drum with modified speakers, David Coll did some work with transducers, and there have been a few other people passing through IRCAM who also work with transducers and plates, such as Savannah Agger and Jean-François LaPorte. However at that time IRCAM didn't actually own any transducers, so it was a new area to explore; even more so for the motors and the logistical questions they posed. Fortunately, the transducers ordered for my project were used by quite a few composers afterwards, and the installation has been reprised numerous times in several different countries. So I would encourage other composers that despite apparent difficulties, you should really follow your dreams.

Robotic fingers, transducers, piano resonance feedback system installed in the piano at Goldsmith's Electronic Music Studio

Patricia with the "cyborg" hand prototype of the string excitation robot